Women’s boxing in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a contradiction as captivating as it is unsettling—a space where empowerment battles for air under the weight of state control. Here, every punch thrown is not just a blow for athletic triumph, but a negotiation of visibility, framed by ideological constraints. The question is no longer whether women can compete, but under what conditions their visibility is allowed. Emerging through paradoxical potential, on one hand, it shatters decades of silence surrounding women’s visibility in a country that has long restricted their autonomy. On the other, it remains a tightly controlled spectacle, carefully curated to fit within the boundaries of acceptability. We might think, here, to the insights on visibility that Judith Butler has given: that our bodies are subject to the power of discourse and representation, which speaks to the fact that visibility is not a simple matter of being seen; it is a constant cultural negotiation. Women’s boxing in Saudi Arabia is no longer confined to the shadows; the process is now underway, but it remains ongoing and is far from fully negotiating its freedom of equal representation.

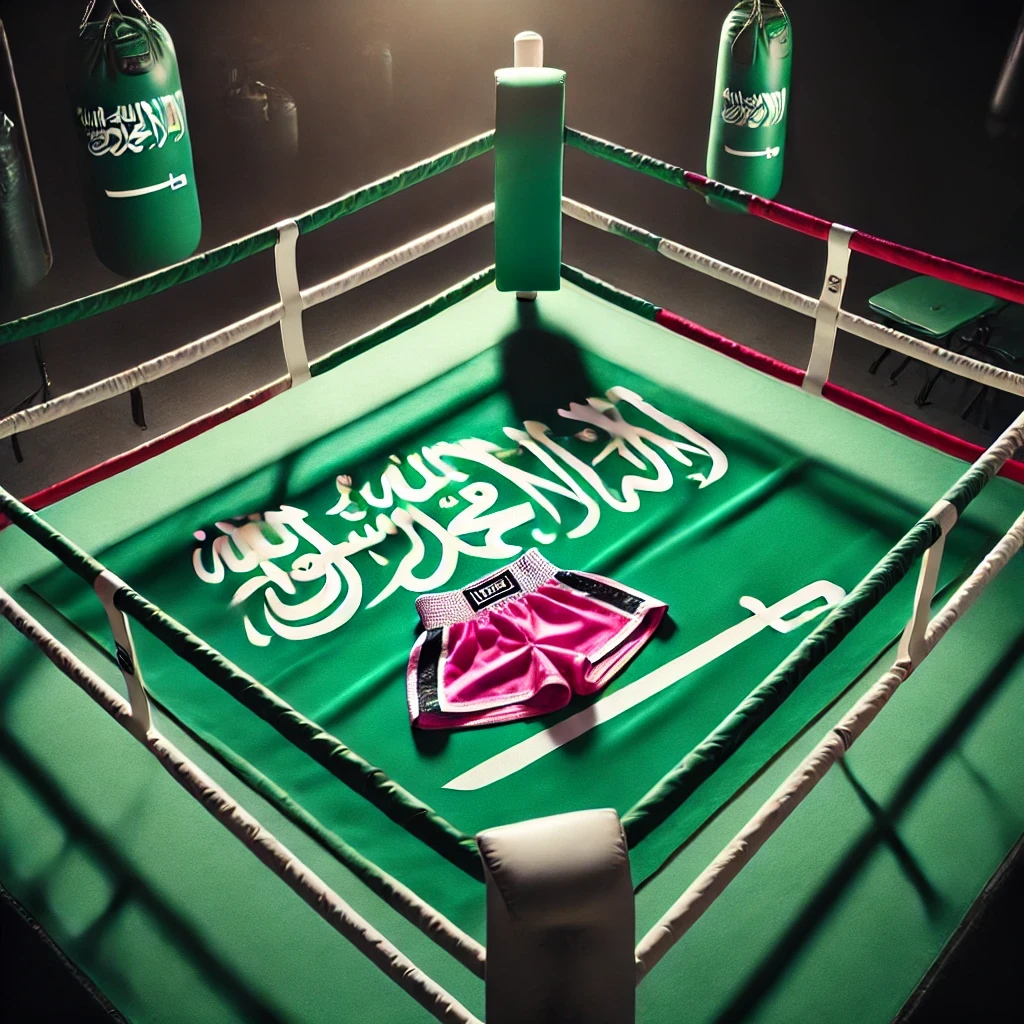

On October 12, 2024, Skye Nicolson and Raven Chapman will step into this complex ring—not just as athletes but as symbols of possibility and limitation. Nicolson, with her impeccable record and technical precision, and Chapman, a fighter known for her relentless drive, will make history as the first women to box at a Riyadh Season event. Nicolson will fight for the WBC Featherweight Title, a milestone that reflects both the progress and paradox of women’s sports in Saudi Arabia. Yet, as they prepare for this historic moment, the question remains: are they pushing the boundaries of women’s liberation, or are they part of a controlled spectacle designed to signal progress without disrupting the status quo?

A History of Firsts: From Ramla Ali to Skye Nicolson

Nicolson’s journey is not without precedent. Two years earlier, Ramla Ali became the first woman to fight professionally in Saudi Arabia, winning her bout in a stunning first-round knockout. Yet, Ali’s victory felt like a flicker – somewhat being rendered as an exceptional moment but ultimately detached from sparking the start of a full and sustained systemic change. Ali was celebrated globally, but the actual structures that keep women’s rights constrained in Saudi Arabia remained largely untouched. This raises an uncomfortable question for Nicolson and Chapman: will their bout be another symbolic victory that fades, or a lasting step toward broader reform?

I feel like it’s a it’s an honour to be in this position to have this opportunity, uh, to be the one, [gestures to Chapman] the one of two to be, um, doing this for the first time for, for women not just women in boxing not just women in sport but women in Saudi as well, um, women all around the world that’ll be tuning in to see this movement

Skye Nicolson, FACE OFF: Skye Nicolson vs. Raven Chapman, Youtube, DAZN Boxing [accessed Oct 11 2024], <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HZ3EuZt9Y3Y&ab_channel=DAZNBoxing>

For Nicolson, this fight holds personal and political stakes. A southpaw with a perfect 11-0 record, including one knockout, Nicolson has built her career on precision and cerebral tactics. She speaks often about her responsibility to inspire future generations of female athletes. “It’s not just about winning a title,” Nicolson said in a recent interview, further adding, “it’s about showing young girls that they can achieve something bigger than themselves, even in places where the odds are stacked against them.” Her words echo a larger truth: in women’s sports, visibility comes with the weight of representation. Nicolson is fighting for herself, but also for a generation of girls watching from the sidelines, dreaming of stepping into the ring.

“I feel like we have a responsibility on our hands to put on a great show and um and make sure that we’re the first of many”

Skye Nicolson, FACE OFF: Skye Nicolson vs. Raven Chapman, Youtube, DAZN Boxing.

Yet, the responsibility of carrying this unusually permitted “visibility” might not be as liberating as it appears. To think of Peggy Phelan, who famously noted, “visibility is a trap”, we might understand how Nicolson and Chapman, in the world of Saudi sports, are encircled and trapped in this balancing act between empowerment and control, progress and restriction.

The Politics of “Boxertopia”

To understand the unique trap of visibility in the Saudi context, we might be led to think of Michel Foucault’s work on heterotopias. He has described heterotopias as spaces of contradiction—real places that represent both freedom and constraint, where norms can be both challenged but also reinforced. Drawing from Foucault’s heterotopias, Nicolson’s and Chapman’s fight represents both transformation and containment. It is a controlled breakthrough—a balancing act between modernity and tradition. The trap becomes balanced by the spectacle of the boxing ring. The boxing ring becomes more than a venue—it’s a symbolic battleground, a “boxertopia”, what we might see as a compensatory space—a way of making up for women’s historical exclusion. Nicolson and Chapman’s fight exists in such a space: a spectacle of empowerment, framed by the boundaries of what is acceptable within Saudi society. It is entangled in both exceptionalism and exceptionality. The boxertopia offers illusionary potential—a space where their achievements are visible, but the deeper ongoing inequalities experienced by Saudi women remain masked.

The trap is, however, becoming more subtle. For example, in early WWE women’s matches hosted in Saudi, wrestlers were required to wear full-body suits to comply with modesty laws. In these instances, the illusion of inclusion is starkly apparent: while women were allowed to participate, their involvement was tightly controlled, their visibility in the form of clothing explicitly curated to align with Saudi Arabia’s ideological enforcement of women’s modesty. Although the strict policing of WWE women’s attire has since lessened, and Nicolson and Chapman won’t face such clothing protocols in the boxing ring, the trap of progress is still carefully constructed waiting to be sprung. To fully buy into the performative display of women’s participation remains complex, as the spectacle inside the ring is still continually presented as exceptional, we are bombarded by narratives that underscore the groundbreaking nature of Nicolson and Chapman visibility. When Nicolson speaks of “responsibility” and the representation of women in sport, the key stakes of future progression are hinted at, to not be trapped into the boxertopia, is to ensure that their visibility is not just enclosed in sentiments of compensation, but real systemic – and stylistic – change.

Visible Stakes and Style

Curiously, by looking at Nicolson and Chapman’s pugilistic style, we can draw further focus to what might be required for us to move beyond the trap of visibility and into the realm of real systemic change. Each of their contrasting styles illustrate something different in the symbolic and cultural responsibility that they also carry. Nicolson, known for her tactical brilliance, will rely on her superior footwork and precision to keep Chapman at bay. “When I’m in there, I set traps,” Nicolson says, referring to her ability to outthink her opponents. “They struggle to deal with my timing and movement.”

Chapman, however, represents a different kind of challenge. Stylistically applauded for her impressive inside fighting style, Chapman thrives in the trenches, she frequently delivers heavy body shots in close quarters and dominates with relentless pressure. “This fight will be the toughest mentally,” Chapman admits, but it seems that beyond mentally, in this fightweek, her strategy is more sophisticated than her described style. Her mentions of disrupting Nicolson’s rhythm and ability to deal with a southpaw stance, suggests that we might see more technical initiation from Chapman, surpassing her previous displays of pure brute force.

“it’s that typical sort of Bull versus Matador, boxer versus fighter, if you look back in history those are the fights that always go down as the really exciting ones because they can be back and forth”

Raven Chapman, FACE OFF: Skye Nicolson vs. Raven Chapman, Youtube, DAZN Boxing.

In some ways, the stylistic coming together of Nicolson and Chapman, technical finesse versus pure aggression, mirrors the broader tension between how ideological manoeuvring can be choreographed. Both Nicolson and Chapman carry their own styles to take over and shape what happens inside the ring – to control and choreograph – but the question remains: how will they be permitted to continue and choreograph women’s representation in future Riyadh season events?

The Illusion of Progress: Saudi Women’s Rights Beyond the Ring

Despite this new visibility that sporting women are being afforded and showcased in the ring, the broader picture of women’s rights in Saudi Arabia demands further interrogation and critique. Vision 2030, the government’s ambitious reform program, presents an image of progress, but the reality is far more nuanced. As our lens zooms into recognising that Saudi is continually changing, or how some might put it, becoming more progressive, the applauding of progression in the form of permitting women to drive and participate in sports, decentralises from important and continuing realities of the male guardianship system still remaining largely intact, restricting their autonomy in other critical areas of life.

Loujain al-Hathloul was the most prominent figure in bringing attention against Saudi Arabia’s driving ban for women, becoming a symbol of resistance against the kingdom’s oppressive gender policies. After experiencing numerous arrests, she was abducted in 2018 while in the United Arab Emirates and forcibly returned to Saudi Arabia, she subsequently endured over 1,000 days in detention before her release in February 2021. Although now free, al-Hathloul remains under a travel ban, which has seen her movements restricted, and her activism suppressed.

The Saudi government continues to present a façade of progressive reform, particularly through Vision 2030, yet repressive tools such as travel bans remain part of the state’s strategy to silence dissent. In March 2022, the passage of the Personal Status Law not only perpetuated the male guardianship system but also codified the expectation that women must obey their husbands, exposing the stark contradiction between symbolic reforms and the oppressive reality.

Dr. Rola El-Husseini’s research highlights how Arab governments, including Saudi Arabia, have adapted aspects of state feminism to further their own agendas, offering limited concessions to women’s rights while preserving patriarchal control. This manipulation serves to project a progressive image while maintaining the state’s grip on power. For activists like Loujain, the state’s use of arbitrary travel restrictions underscores the ongoing struggle for genuine change. The Specialized Criminal Court (SCC) continues to target human rights defenders, one further case in a current petition is that of Salma al-Shehab, a Leeds University student sentenced to 27 years in prison over tweets supporting activists opposing the guardianship system. These stories reflect the larger struggle for real freedom of expression and autonomy in Saudi Arabia, where women who dare to challenge the system often face dire consequences.With no legal avenue for appeal, those affected are left trapped, their movements curtailed and their voices stifled, knowing that any attempt to resist might endanger both themselves and their families.

The boxing ring may be framed as a space where women can showcase their strength, but outside of it, if legally questionable rules such as travel bans are being applied to limit activism and oppositional opinion, we must question why the strength of Saudi women activists are being controlled and restricted and how the presence of women’s boxing functions as a tool of performative empowerment.

Performative Empowerment or Real Change?

For Nicolson, the stakes go beyond the personal. She is aware that her fight is part of a larger narrative of progress—one that may be more symbolic than substantive. Empowerment has become the cultural currency of feminism, if we are to follow the work of Sarah Banet-Weiser, but excessive applause for empowered narratives risk turning women’s boxing into a depoliticized display of faux-feminist activism, relegating it to mere commodity and ineffective spectacle. Nicolson and Chapman’s visibility and presence are a form of activism, but whether it can operate as effective feminism leading to real change or merely reinforce the state’s control over women’s representation remains uncertain.

As Nicolson and Chapman prepare to step into the ring, they do so as athletes, yes—but also as symbols of a complex negotiation between empowerment and control, visibility and restriction. The feminist boxertopia they inhabit is fragile, a space where progress is visible but tightly managed. Whether this fight will mark a lasting shift or simply another fleeting spectacle is a question that lingers, much like the oppressive desert heat that surrounds them.

Conclusion: Boxing for Liberation, or Fighting Within the Lines?

Ultimately, Nicolson and Chapman’s fight is more than just a contest for a title—it reflects the broader tension between progress and illusion in Saudi Arabia’s treatment of women. While the opportunity to see women step into the ring in Riyadh has drawn both applause and criticism, it offers hope for a future where women’s empowerment moves beyond a controlled spectacle of athleticism. Ideally, these performances under Vision 2030 could signal a pathway toward a reality where women’s rights are fully realised, not just in sports, but across all arenas of life.

“it’s huge there’s not many things now that can go down in history you know most things have been done so to be part of something that that will be in the history books forever is is is massive like really humbling and just proud to be part of that as well part of like I said one of the two doing that is just yeah just feel very grateful and honoured”

Raven Chapman, FACE OFF: Skye Nicolson vs. Raven Chapman, Youtube, DAZN Boxing.

What is certain, however, is that Nicolson and Chapman are fighting for more than just themselves. They are boxing in a space where the very act of fighting is a statement, one that challenges the ideological lines drawn around them, even if the boxertopia cannot yet breach into the systemic potential to erase those very lines of oppression and inequality.